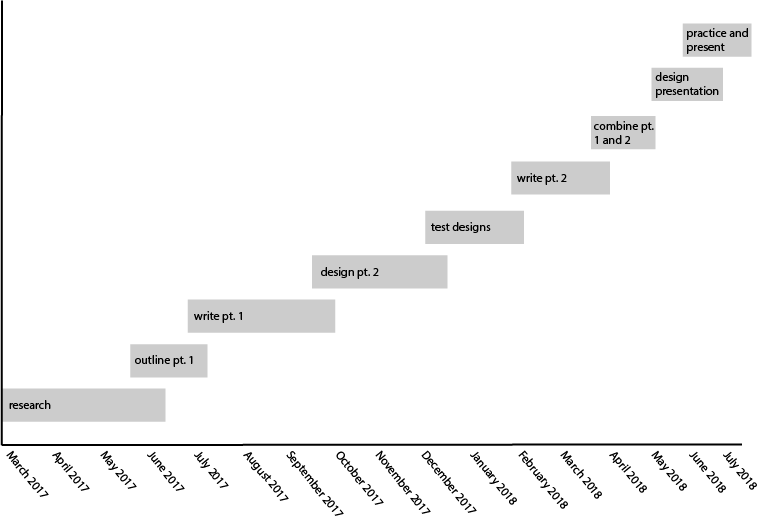

Conversation is a central metaphor in the design of human-computer interaction: from the oldest programming "languages" in binary, to today's voice-commanded interfaces that can respond to the spoken word. Conversational interface agents are pieces of software designed to help people use computers by structuring their interactions as though they are interacting with another human instead of a machine. These agents can offer information, navigational cues, and entertainment to facilitate computer use, and are often personified, given a name and some representation of embodiment. The design of these anthropomorphic agents' embodiments will be the subject of my research. Designing the embodiment of conversational agents raises many questions: how does representing a conversational agent with an avatar containing humanoid face or body features make them more effective? What are the design choices that create the most comfort, ease of use, and enjoyability in engaging with software, and in which contexts? How do the embodied politics of gender, race, and sexuality affect the way that these agents are designed? By performing analyses of existing conversational agents, and the way that the technology and design of these agents has evolved over time, I hope to answer some of these questions and create an effective framework in which to test my findings by designing my own conversational agents.

The background research for analyzing conversational agents necessarily begins in the era of personal computing, the early 1990s. Before this point, computers were generally used by specialists and programmers, whose system images (Norman, 2013) of how computers worked were more accurate to the actual mechanisms of hardware and software. When computers began to enter the homes of non-programmers, design metaphors evolved to facilitate ease of use for casual users, whose system images do not contain any knowledge of hardware or software. In this period, we see the development of the graphical user interface, which contains many visual metaphors that persist to this day, such as a file system (or folders) for data storage and retrieval, or simulated paper for word processors. These translations of other objects into the interface of the computer illustrate how the computer as a tool simultaneously becomes easier to use, and harder to understand how it works. (Grudin, 1990)

Many researchers have noted the phenomenon of computers being anthropomorphized, possibly due to the opacity of their systems: because we don't understand how it works, the computer seems to have a mind of its own (Hybs, 1996). Human-computer interface designers use the conversational agent to bridge this gap. The conversational agent speaks directly to the user, anticipating their needs and lack of knowledge of the computer's inner workings, to help them accomplish whatever task they are using the computer for. Both appearance and functionality play a role in whether the user trusts and successfully utilizes the conversational agent: notable historical examples include Microsoft's Bob and the infamous Clippy. (Koda, 1996)

After collecting examples of conversational agents from the last two or three decades and analyzing the discourse surrounding them amongst the general population and in academia, I intend to compile an analysis of the most successful and unsuccessful design features of these conversational agents. These features include how realistically they are rendered, their avatars' humanity, perceived gender, expressiveness and emotion, animation, placement and context within a web or software interface, and accessibility features. Combining this visual analysis and literature review of studies about human-computer interaction and conversational interfaces with an implementation of web design, I intend to create some conversational agents myself, adhering to the best practices learned from analyzing the examples.

My research is limited in scope by two key features that separate a certain type of conversational agent from other conversational tools for human-computer interaction. The first feature that limits my scope is that the conversation between human and agent should be text-based. The reason that I find this an intriguing limit to impose is because of its historical precedent: text-based conversations with computer systems go as far back as Alan Turing's famous test of machine intelligence. Incorporating text also poses an interesting problem in user interface design, and centers conversation as a visual metaphor, as opposed to a literal conversation occurring with speech. There is a lot of material to explore in how verbal and nonverbal conversational functions and cues are represented and executed using only the keyboard and screen. The second limitation is that there must be a representation of the agent's embodiment as an essential part of the conversational interface. For example, the ELIZA chatbot is one of the best known historical examples of a conversational agent, because it was the most advanced at its time and came close to passing the Turing test. A female embodiment may be implied by the name, but beyond that there is very little design to ELIZA besides her information architecture, and therefore chatbots like ELIZA, which don't have any embodied representation to speak of, will be excluded.

Based on the findings of this research, I will design new conversational agents. These may include redesigns to improve unsuccessful historical examples, or entirely new agents to fill contemporary needs. Because the agents can be web-based, these new conversational agents could be made publicly available on the internet for testing by a large audience, whose reactions and use of the agents could be observed and quantified. It would be a simple matter to track mouse behavior, clicks, and record the conversations people have with these agents. Another method of analyzing how users respond to the agents could be to ask them to complete a survey before or after encountering the agent. The most difficult part of conducting research with new conversational agents will be coming up with realistic scenarios or contexts in which to place them, but these use cases should become clear through the research process.

The expected outcome of the visual analysis and literature review portion is to find that the design of conversational agents and their chat interfaces has not significantly progressed in the last 20 years. I expect to find trends towards more advanced human-like designs, more female conversational agents, and away from anthropomorphized objects. I also expect that conversational agents will be used in many contexts, but for the most part will be used for entertainment, for replacing software tutorials, and as customer service assistants. The expected outcome for the experiments with new conversational agents will have to be determined during the design process.